Introduction

Why I Wrote This

This isn’t about nostalgia.

It’s about memory — and what happens when it’s erased.

It’s about the people who built things.

The ones who stayed.

The ones who believed.

It’s about what was lost.

And what was taken.

I wrote this not to settle scores, but to set the record straight.

Because some stories don’t get told.

Some names get left out.

And some truths are too quiet to survive without someone writing them down.

This is me writing it down.

This is not a biography. It’s a record. A tribute. A reckoning.

Section I: My Father, The Builder

My Father’s Journey Through American Hospitality: From Dairy Farms to Drive-Thrus:

My father, Guy W. Van Dyke, was born on August 31st, 1933 — in the shadow of the Great Depression, on land that demanded more from a boy than most men give in a lifetime. He spent his early years on a dairy farm, where the days started before sunrise and ended only when the work was done. It wasn’t an easy life, but it was an honest one. It taught him discipline, endurance, and the quiet pride of doing things right the first time.He excelled in school — not just academically, but socially. He was involved, active, and respected. He wasn’t the loudest voice in the room, but people listened when he spoke. That would become a theme throughout his life.

Then came Korea. Like many young men of his generation, he was sent overseas and came back changed. Not broken — just sharpened. More focused. More determined. He didn’t talk much about what he saw there, but you could feel it in the way he carried himself. He had seen the world at its worst, and he came home ready to build something better.

|

| [Dad on a Troop Ship] |

He met my mother, and they married. He worked as an insurance agent and held down other jobs, as veterans often did — not because he had to, but because he knew how to. He was never idle. He was always moving forward.

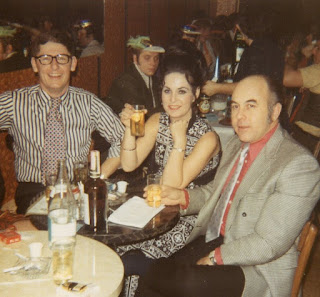

|

| [Mom and Dad in the LJS Early Days] |

Then came the opportunity that changed everything:

A family connection to Jerry’s Restaurants, and to Jerrico, Inc., in Lexington, Kentucky.

It wasn’t a gift.

It was a chance.

And my father took that chance — and ran with it.

|

| [An actual Jerry's Employee Handbook] |

|

| [Warren Rosenthal] |

At Jerrico, he rose through the ranks with quiet determination. When the company began developing a new seafood concept — what would become Long John Silver’s — he was there from the beginning. Before the first store opened. Before the name was finalized. Before Jim Patterson — then just a Jerry’s franchisee — was even brought in. Patterson would later become the first president of LJS, but the groundwork — the vision, the planning, the early execution — was already underway. My father was part of that foundation.

When the company needed someone to expand LJS into scaled nationwide operation from the Texas region, my father didn’t hesitate. He packed up his wife and three kids and moved us to Dallas in 1969–70. That wasn’t a supporting role. That was a leap of faith. And he made it count.

Long John Silver’s didn’t begin with Jim Patterson.

It began with Jerrico Inc., the same company behind Jerry’s Restaurants, led by Warren Rosenthal. In 1969, Jerrico launched Long John Silver’s in Lexington, Kentucky, my hometown, where I was born — not as a side project, but as a full-scale concept backed by the company’s resources and vision.

Jim Patterson was there, yes — a Jerry’s franchisee who joined the effort and later became the first president of LJS.

But he wasn’t the founder.

I know what the company’s official story says now.

But I remember how it really happened.

I was there.

I wrote it down in my diary.

Yeah — a boy with a diary.

But I’ve always been a writer.

By the early 1970s, Long John Silver’s was scaling fast — hundreds of stores across the country. Texas wasn’t where it started.

But it was where it grew.

|

| [Dad and his Long John's Team] |

Dad served in the upper management branches, overseeing site selection, construction, and expansion across the Southwest. He built that region from the ground up — not just the stores, but the teams, the systems, the culture. Later, after Patterson left and the company shifted, my father became President of the Texas region — a title that reflected what he had already been doing for years.

He stayed loyal to Rosenthal, even as others followed Patterson out the door. He believed in building something lasting. And he did.

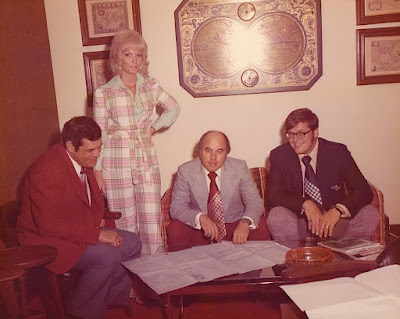

|

| [Planning Meeting at LJS Offices] |

After Long John Silver’s, he helped shape Grandy’s Fried Chicken — a Texas-based comfort food chain that peaked in the 1980s with nearly 200 locations nationwide. He also worked with Tom Sawyer’s Old Fashioned Krispy Chicken, a lesser-known but ambitious fried chicken concept that began in California in 1978 (and later found a second life in the Philippines). These were regional brands with big aspirations — and for a time, they carved out real space in the fast food landscape.

I vividly remember living out of a hotel room in Gallup, New Mexico — just me, my sister Darcy, and my dad — during our summer vacation, while he got a Grandy’s store up and running.

It wasn’t glamorous. It wasn’t easy.

But that’s what building looked like.

Not boardrooms. Not press releases.

Just long days, late nights, and a family making it work while he made something real.

When we moved to Southern California for the Tom Sawyer’s Chicken venture, we landed just off the Sunset Strip — a strange, glittering place where restaurants didn’t just serve food. They hired actors. Models. People with headshots in their glove compartments. The line between server and screen test was paper-thin.

We met celebrities.

We went to a practice run and taping of The Gong Show with Chuck Barris.

Not because we were celebrities — but because we were in the orbit of a business that treated fried chicken like a casting call.

From there, he went on to executive leadership roles with Po Folks, People’s Restaurant, IHOP, and Chi-Chi’s — each a different chapter in the evolving story of American dining.

At People’s Restaurant, he first served as President, helping guide the brand’s growth and direction. But he didn’t just lead from the top — he believed in the concept enough to become a franchisee, opening four stores of his own. It was a bold move, rooted in belief and commitment.

Unfortunately, corporate changes and mismanagement at the top would eventually unravel the chain, leaving many — including my father — to absorb the fallout.

I remember Po Folks a little. I was off doing my own thing during the IHOP years. I was around for the Chi-Chi’s years — which, honestly, was a great experience.

And then, in 1985, when Jim Patterson launched Rally’s, guess who he called first?

My father.

He became the first employee of Rally’s — the first person Patterson trusted to help build something new.

And once again, my father delivered.

|

| [Seth Green - Rally's Cha-Ching Commercial] |

That’s when the carpetbaggers showed up — the kind of people who show up when the money’s good, not when the work is hard.

They weren’t there to build.

They were there to cash in.

And then Patterson was forced out. He was maneuvered out — quietly, but unmistakably. And slowly, almost imperceptibly at first, things began to disintegrate. Leadership changed. Priorities shifted. The soul of the company — the one my father helped shape — began to erode.

Rally’s was the one that hit my dad the hardest. He was older then, trying to save it — and his investments — from the inside. Maybe he hung on too long. Maybe he believed too much. Maybe he was too loyal. In the end, it more or less ruined him.

My father didn’t just help build companies — he helped define them.

And in the end, every single one faltered after he left — or was no longer in charge.

That’s not a coincidence. That’s a legacy.

He wasn’t just a name on an organizational chart.

He was the steady hand — the workaholic, the heavy, the stabilizing force.

The one who made things work.

And when he was gone, cracks began to form.

He never thought that about himself. But the truth is, he was the difference.

Loyal. Driven. So loud sometimes he would bring the roof down and make the angels weep and cower. He was as hard as he had learned to be in Korea.

Do it right, or get out. That was my dad’s philosophy.

Not Politically Correct in these days — but look at the state of businesses today.

I wasn’t always there. I didn’t see every deal, every decision, every late night. There are other restaurants he helped grow, but I cannot recall them all.

But I saw enough to know: my father was more than most people will ever realize. And the places he helped build? They weren’t just restaurants. They were reflections of his values — steady, honest, and intended to last and to succeed. When he was there, they always did — except for the last, and that was beyond his control.

Section II: The Bridge

Carrying the Legacy, Confronting the Cost

I didn’t set out to follow in my father’s footsteps. But somehow, I found myself walking a parallel path — not in title, not in work, but in spirit. My destiny included Jim Patterson too.

|

| [Jim Patterson] |

I joined Rally’s during its heyday, when the “Cha-Ching” commercials were still echoing across the country and the company felt like it was on the edge of something big. I was part of the Information Systems department, and I loved that job. I lived it.

I wasn’t just punching a clock. I was solving problems, building systems, helping keep the whole thing running. I worked long hours — not because I had to, but because I wanted to. Because I believed in what we were doing. Because I believed in the people I worked with. And maybe, deep down, because I believed in what my father had helped start.

But belief doesn’t always protect you.

I believed in the company.

I was an employee — and an investor.

But I saw things. So many things.

Waste. Excess. Decisions that made someone money — but not the stockholders. Not the employees.

There was the time they installed 21-inch CAD-grade color CRT monitors in the drive-thru lanes — not touchscreens, not ruggedized kiosks, just top-of-the-line computer displays. These were the kind of monitors used for engineering workstations, not burger orders. They cost at least $1,500 apiece, even with the vendor deal we had. Most businesses couldn’t afford them. Most homes had never seen one.

And we stuck them outside.

In custom-built wooden boxes.

In full Southern sun.

No shade. No cooling system. Maybe a fan, if someone remembered.

Just glowing green text, slowly cooking in the heat — until they dimmed, warped, or died.

It was a perfect metaphor: expensive, impressive, and completely unsuited to the environment we were actually in.

The monitors didn’t run Windows themselves — they were just dumb terminals. But they were wired to in-store computers that did. Which meant that sometimes, instead of showing a burger order, the monitor would proudly display a Blue Screen of Death.

A customer would pull up expecting fries and a drink, and instead be greeted by a fatal exception error.

It was a tech flex, not a practical solution — the kind of thing that happens when someone up top says,

“Wouldn’t it be cool if…”

without ever asking,

“Will it actually work?”

No thought to cost. No plan for value recovery.

Just the allure of something that looked impressive — for a minute.

As long as it turned heads, that was enough.

And hey — if it didn’t work out?

They could always take one home.

It was, after all, for work.

Now put those expensive monitors in 500 restaurants, with double drive-thru lanes, meaning two wooden boxes, two monitors, two wiring setups per store — and just imagine that expense.

And that waste.

In the end, we had to pull them out of all those stores.

They didn’t last long.

Or they were stolen right out of the box.

And then there were the out-of-state contractors.

Programmers brought in to build our custom point-of-sale system — not to improve it, not to integrate with proven platforms like Cisco, but to reinvent the wheel. From scratch. With our logo on the screen.

They weren’t Rally’s employees. They came from a firm out of state — Florida, maybe Boston — flown in every week or two to work on-site in Louisville. Monday to Friday. Flights, hotels, rental cars, per diems — all of it, every week. The cost of that alone could’ve funded a full-time, in-house development team. Maybe two.

They’d arrive, settle into their cubicles, and start coding — often without a full understanding of the systems we already had in place. We’d spend half the week explaining what we needed, and the other half cleaning up what didn’t work. Then they’d fly home, and we’d do it all again the next Monday.

It wasn’t their fault. They were doing the job they were paid to do.

And it didn’t matter if it took years — refining, recoding, redoing.

Because the people in charge weren’t up to speed on modern tech.

They just wanted something that looked impressive. Something they could point to and say,

“See? We built that.”

It was a system that valued outside contracts over internal continuity.

A culture that prized appearances over practicality.

And a leadership style that confused novelty with innovation.

It was the perfect metaphor for what Rally’s was becoming:

A company that once ran on hunger and instinct, now running on invoices, buzzwords, and burn rates.

Ego funding. Cash cow spending. Waste.

Not a great strategy for a company selling cheap hamburgers.

Mostly, all he did was undermine.

Burt Sugarman, a film producer, was one of the people who forced Patterson out. He became CEO after Patterson. Then he started buying up competing restaurant companies like he was picking up seashells on the beach — Maxie’s, Snapps, Zipps — and hemorrhaging money in the process.

They bought those brands like they were collecting trading cards.

I worked there — and I never saw a single one of those stores in person.

That new executive, with no discernable restaurant or technical background? He wanted to scrap everything.

Years of work. Custom systems. Microsoft-based tools we had built, refined, and relied on.

His vision? Convert the entire company to Macintosh.

Not just marketing. Not design.

Everything.

I fought it. Tooth and nail.

I built spreadsheets — cost comparisons, conversion timelines, training estimates, hardware expenses. I met with the President of the company. I wasn’t alone. No one in IT wanted to throw away everything we’d built just to chase a trend. We were Microsoft certified, deeply embedded in the systems we had. We knew what worked — and we knew what didn’t.

And this? This didn’t.

The Mac conversion never happened. We stopped it. We saved the company from a disaster it didn’t even see coming.

He hated me for that. I didn’t care. I didn’t care for him either.

He reminded me of Brice Cummings (played by John Glover) from Scrooged (1988) — the kind of slick character who shows up trying to take the boss’s job. Slithering in, charming, handsome, with an agenda.

All flash, no grounding.

In the end, I think he said, “It was just an idea. No big thing.”

Riiight.

And if you want to know why I didn’t name him here, it’s because I still loathe him to this day.

So many years later.

Decades later.

Eh.

If I saw him on the street today, I wouldn’t spit in his face.

If he spoke to me, I’d smile and say,

“Go f*** yourself, you chancer.”

Well, I gotta be honest.

After that, things started to unravel, for me, and the company.

Not all at once. Not in some dramatic collapse. Just a slow, steady erosion — of trust, of purpose, of the kind of people who built Rally’s in the first place.

You could feel it in the hallways. In the silence after meetings. In the way people stopped decorating their desks. In the way no one made eye contact when someone’s badge stopped working.

And me? I kept doing the work. I kept showing up. But I knew. I knew my time was running out.

A few months after I helped kill the Mac conversion, I uncovered something else — embezzlement. Duplicate invoices. Suspicious billing. I followed the trail, built the case, and brought it to my VP. He listened. He nodded. He called in Asset Protection. And then… nothing.

I was told to let it go.

So I did.

And a few months later, they let me go too.

The reason they gave was flimsy. It didn’t matter. The writing had been on the wall for a while. I wasn’t the kind of person they wanted around anymore — someone who remembered how things used to be. Someone who asked questions. Someone who told the truth.

For months afterward, people kept calling me — asking how to fix this, where to find that, how to make something work. Eventually, I told them:

“I don’t know. Stop calling me.”

One friend told me they hired four people to replace me. That sounds like an exaggeration. It’s not.

I was even told — quietly, off the record — that my job might be available again.

I declined.

I had already learned the lesson: loyalty doesn’t always go both ways.

But I don’t regret it. I did the right thing. I told the truth. I worked hard. I built something that mattered. And when it was time to walk away, I did — with my integrity intact.

Section III: The Legacy

What We Carry, What We Let Go

The Patterson connection didn’t end with me.

Years later, two of my nephews — Stephen, and then Ben — began working for him too.

The next generation stepping onto the same path, at least for a while.

None of us are on it anymore.

That’s the thing about legacy.

It’s not just what you inherit — it’s what you choose to keep.

And sometimes, it’s what you choose to accept.

For my father, legacy was loyalty. It was showing up. Building something that would last. He believed in people. He believed in systems. He believed that if you did the work, the rewards would follow.

For me, legacy became something else. It became truth.

Telling it. Preserving it. Refusing to let it be rewritten by the people who profited from silence.

Patterson drifted away.

We haven’t seen or heard from him in… forever.

Not after the heart attacks.

Not after the dementia diagnoses.

Not a phone call.

Not even a Christmas card signed by a secretary.

And maybe that’s the final truth of it:

For some, loyalty only matters when there is benefit.

Rosenthal was a builder. Loyal. Grounded. He didn’t just start things — he stayed to see them through. He believed in people. He believed in the long game. He was loyal to his people.

Patterson was a starter. He had vision. He could see what wasn’t there yet and will it into being. But he didn’t stay. He didn’t build. He moved on. He cashed out, or cashed in, and the “family” he said his workers were all part of? That was never the truth.

|

| [Burt Sugarman and wife Mary Hart] |

But the cost?

That never left.

It reminded me of the turquoise jewelry my parents bought on the reservation in New Mexico — thousands of dollars’ worth, once prized, now nearly worthless overnight.

The silver still held some value.

But the stone? The thing that once made it special?

That had been replaced. Replicated.

Devalued by something cheaper, faster, easier to mass-produce.

Just like the restaurants.

Just like the people who built them.

And me?

I lost money. I lost friendships. I lost time I’ll never get back.

But more than that, I lost the illusion that hard work and loyalty were enough.

Now I’m his caregiver.

I manage the pills, the appointments, the bills.

I stretch every dollar. I navigate the same broken systems that failed him — and so many others — when they needed protection the most.

We’re not alone in this.

There are thousands of families like ours — people who did everything right, only to be left behind when the people at the top cashed out and moved on.

And the ones who profited?

They want to rewrite history.

They want to tell a cleaner version — one where the collapse was inevitable, or nobody’s fault, or just the way business works.

But I was there.

I kept records.

I wrote it down.

And I will not let them erase what happened.

Because this isn’t just about Rally’s.

It’s about what happens when loyalty is exploited.

When workers are treated like tools.

When small investors are sold down the river.

And when the people who built the foundation are left out of the story.

My father’s name isn’t on any of those company websites or in their histories.

Those have been cleared out, cut down, over the years.

But here — at least here — he will be remembered.

I do not much care if I am remembered,

except for perhaps my writings,

my creative efforts,

and my staunch belief in loyalty.

Yes, I still have that belief.

But I am more cautious now.

Mark W. Van Dyke

📜 Fair Use & Author’s Note

Images included in this work are used under the doctrine of fair use for the purposes of commentary, criticism, and historical documentation. All visual materials remain the property of their respective copyright holders. If you are the rights holder of any image and believe its use here is inappropriate, please contact me for prompt removal or attribution.

This work is a personal narrative.

The events, reflections, and interpretations presented are based on my own experiences, perceptions, and contemporaneous records, including personal diaries and professional documentation. While every effort has been made to present these memories truthfully, they are, by nature, subjective.

No comments:

Post a Comment